Life, in all its intricate forms, from the simplest bacterium to the most complex human, is built upon a foundation of fundamental organic molecules – biomolecules. These are the essential chemical compounds synthesised by living organisms, playing pivotal roles in structure, function, and regulation within cells. Understanding biomolecules is crucial not only for biology enthusiasts but also for civil service aspirants, as it underpins many aspects of health, environment, and scientific policy.

What are Biomolecules?

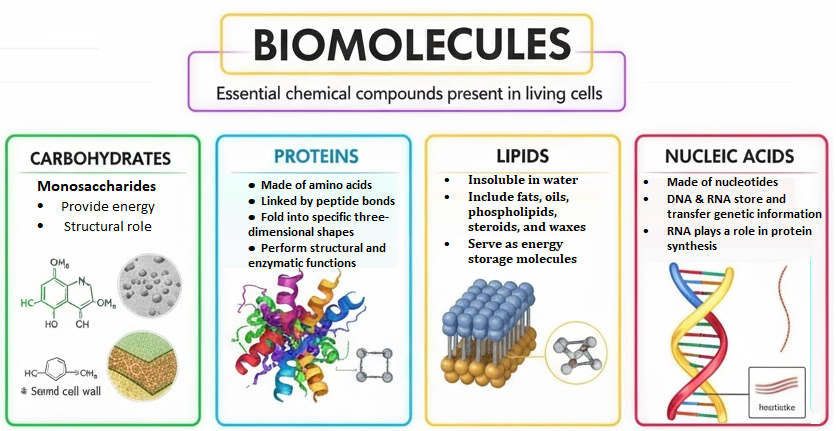

Biomolecules are organic molecules produced by living organisms. They primarily consist of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. Their unique structures and properties allow them to perform a vast array of functions vital for life. Broadly, biomolecules are categorised into four major classes: Carbohydrates, Proteins, Lipids, and Nucleic Acids. Each class has distinct characteristics and specific roles within the cell.

The Four Pillars of Life: Major Classes of Biomolecules

1. Carbohydrates: The Energy Providers and Structural Supports

Carbohydrates are perhaps the most abundant biomolecules on Earth, serving as the primary source of energy for most living organisms and playing significant structural roles. Their name literally means “hydrated carbons,” reflecting their general chemical formula (CH₂O)n.

Structure: Carbohydrates are broadly classified based on their size and complexity:

- Monosaccharides (Simple Sugars): These are the simplest carbohydrates, serving as the basic building blocks. Examples include glucose (the main energy currency of cells), fructose (found in fruits), and galactose (found in milk). They typically have 3 to 7 carbon atoms.

- Disaccharides: Formed when two monosaccharides are joined together by a glycosidic bond. Common examples are sucrose (table sugar = glucose + fructose), lactose (milk sugar = glucose + galactose), and maltose (malt sugar = glucose + glucose).

- Polysaccharides (Complex Carbohydrates): These are long chains of many monosaccharide units linked together. They can be hundreds or even thousands of units long.

Functions:

- Primary Energy Source: Glucose is the central molecule in cellular respiration, where its chemical energy is harvested to produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the immediate energy currency of the cell.

- Energy Storage:

- Starch: The primary energy storage polysaccharide in plants, composed of amylose and amylopectin. Grains, potatoes, and legumes are rich sources.

- Glycogen: The animal equivalent of starch, stored mainly in the liver and muscles, providing a readily available glucose reserve.

- Structural Support:

- Cellulose: A major component of plant cell walls, providing structural rigidity. It is the most abundant organic polymer on Earth. Humans cannot digest cellulose, but it is vital as dietary fiber.

- Chitin: Forms the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans, and cell walls of fungi.

Example: When you eat a potato, you are consuming starch. Your digestive system breaks down this complex polysaccharide into glucose, which is then absorbed into your bloodstream to fuel your body’s activities. Plants, on the other hand, use cellulose to maintain their upright structure against gravity.

2. Proteins: The Workhorses of the Cell

Proteins are arguably the most versatile and functionally diverse biomolecules. They are essential for virtually every process within living cells, acting as enzymes, structural components, transporters, hormones, and antibodies.

Structure: Proteins are polymers made up of smaller units called amino acids. There are 20 common types of amino acids, each with a unique side chain (R-group).

- Amino Acid Structure: Each amino acid has a central carbon atom bonded to an amino group (-NH₂), a carboxyl group (-COOH), a hydrogen atom, and a variable R-group.

- Peptide Bonds: Amino acids link together via peptide bonds, forming long chains called polypeptides.

- Protein Folding: A polypeptide chain folds into a specific three-dimensional structure, which is crucial for its function. This folding occurs at four levels:

- Primary Structure: The linear sequence of amino acids in the polypeptide chain.

- Secondary Structure: Local folded structures like alpha-helices and beta-pleated sheets, formed by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms.

- Tertiary Structure: The overall three-dimensional shape of a single polypeptide chain, resulting from interactions between R-groups (hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, disulfide bridges, hydrophobic interactions).

- Quaternary Structure: (Optional) Occurs when multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) associate to form a functional protein complex (e.g., haemoglobin).

Functions:

- Enzymes: Act as biological catalysts, accelerating nearly all biochemical reactions in the body (e.g., digestive enzymes like amylase, proteases).

- Structural Components: Provide shape and support to cells and tissues (e.g., collagen in connective tissues, keratin in hair and nails).

- Transport: Carry substances across cell membranes or throughout the body (e.g., haemoglobin transports oxygen, membrane channels transport ions).

- Signaling/Hormones: Transmit messages between cells and regulate physiological processes (e.g., insulin regulates blood sugar).

- Defence: Antibodies (immunoglobulins) identify and neutralise foreign invaders like bacteria and viruses.

- Movement: Proteins like actin and myosin are essential for muscle contraction.

Example: Imagine enzymes as tiny molecular machines that tirelessly build and break down molecules within your body. Without them, most life-sustaining reactions would occur too slowly to support life. Collagen, another protein, provides the framework for your skin, bones, and tendons, giving them strength and flexibility.

3. Lipids: Diverse Molecules for Energy Storage, Structure, and Signalling

Lipids are a diverse group of molecules characterised by their insolubility in water (hydrophobic nature) and solubility in organic solvents. They do not typically form polymers like the other biomolecules.

Structure: Key types of lipids include:

- Fats and Oils (Triglycerides): Composed of a glycerol molecule attached to three fatty acid chains. Fats are solid at room temperature (e.g., butter), while oils are liquid (e.g., olive oil).

- Phospholipids: Similar to triglycerides but with one fatty acid replaced by a phosphate group. They have a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and two hydrophobic (water-fearing) tails.

- Steroids: Characterised by a carbon skeleton consisting of four fused rings (e.g., cholesterol, hormones like testosterone and oestrogen).

Functions:

- Long-Term Energy Storage: Lipids store more energy per gram than carbohydrates, making them efficient reserves. Adipose tissue (body fat) stores triglycerides.

- Membrane Structure: Phospholipids are the primary components of cell membranes, forming a flexible lipid bilayer that regulates what enters and exits the cell.

- Insulation and Protection: Adipose tissue provides thermal insulation and cushions vital organs.

- Hormones: Steroid hormones act as chemical messengers, regulating various physiological processes.

- Vitamins: Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) are lipids or derived from lipids and play crucial roles in metabolism.

Example: The cell membrane, the boundary of every cell, is a dynamic structure primarily composed of phospholipids. These molecules arrange themselves into a double layer (bilayer) with their water-loving heads facing outwards and their water-fearing tails tucked inside, effectively creating a barrier that controls the cellular environment.

4. Nucleic Acids: The Bearers of Genetic Information

Nucleic acids are the information-carrying biomolecules, responsible for storing, transmitting, and expressing genetic information. They are paramount for heredity and the synthesis of proteins.

Structure: Nucleic acids are polymers made up of repeating monomer units called nucleotides. Each nucleotide consists of three components:

- A five-carbon sugar: Deoxyribose in DNA, ribose in RNA.

- A phosphate group.

- A nitrogenous base: Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), Thymine (T) in DNA; Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), Uracil (U) in RNA.

Two Major Types:

- Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA): A double-stranded helix, DNA contains the genetic blueprint of an organism. The two strands are held together by hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs (A with T, G with C).

- Ribonucleic Acid (RNA): Typically single-stranded, RNA plays various roles in gene expression, primarily in converting the genetic information from DNA into proteins.

Functions:

- Storage of Genetic Information (DNA): DNA stores all the hereditary information required for the development, functioning, growth, and reproduction of an organism.

- Transmission of Genetic Information (DNA & RNA): DNA is replicated before cell division, ensuring accurate transmission of genetic information to daughter cells. RNA molecules (mRNA, tRNA, rRNA) are crucial for translating the DNA code into proteins.

- Gene Expression (RNA): RNA molecules carry instructions from DNA to the ribosomes (where proteins are made) and assist in the assembly of amino acids into proteins.

Example: Think of DNA as the master blueprint kept securely in the nucleus of a cell. When a particular protein needs to be made, a copy of the relevant section of the blueprint (a gene) is made in the form of RNA (messenger RNA or mRNA). This mRNA then travels out of the nucleus to the “protein factories” (ribosomes) in the cytoplasm, where its instructions are read and used to assemble the correct sequence of amino acids to build the protein.

How Biomolecules Work Together: The Symphony of Life

The remarkable complexity and efficiency of living systems arise not from the isolated functions of these biomolecules but from their intricate and coordinated interactions. They form a biological symphony where each component plays a crucial role:

- Enzymes (Proteins) Regulate Biochemical Reactions: Almost all metabolic reactions, from breaking down food to synthesising new molecules, are catalysed by enzymes. These protein catalysts ensure that reactions occur at speeds compatible with life. For instance, digestive enzymes break down complex carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids into smaller units that can be absorbed.

- DNA Replicates to Pass Genetic Information: The integrity and continuity of life depend on the accurate duplication of DNA. Before a cell divides, its DNA undergoes replication, a process guided by various enzymes (proteins) and utilising energy derived from carbohydrates and lipids, ensuring that each new cell receives a complete set of genetic instructions.

- Transcription and Translation Produce Proteins: The flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA (transcription) and then from RNA to protein (translation) is central to life. This “Central Dogma” involves nucleic acids carrying the code, and various proteins (enzymes, ribosomal proteins) executing the synthesis. The resulting proteins then perform the vast majority of cellular functions, including constructing more biomolecules.

- Combined Activity Maintains Cellular Organisation: Lipids form the structural basis of cell membranes, providing compartments where specific biochemical reactions can occur. Proteins embedded within these membranes control transport and receive signals. Carbohydrates on the cell surface act as recognition markers. Nucleic acids direct the entire assembly and maintenance. This collaborative effort ensures the precise organisation and function of cells, tissues, and ultimately, the entire organism. For example, a cell needs energy (from carbohydrates/lipids) to power protein synthesis (directed by nucleic acids) that produces structural proteins (for cell integrity) or enzymes (to process more nutrients).