Introduction — Why this matters for GS Paper IV

Integrity is a foundational virtue for public servants: it underpins public trust, the legitimacy of institutions, and ethical decision-making. For UPSC GS-IV, understanding how integrity differs from neighbouring concepts such as honesty, and seeing how both play out in real administrative life, helps answer value-based and case-scenario questions with clarity and nuance.

1. Definitions

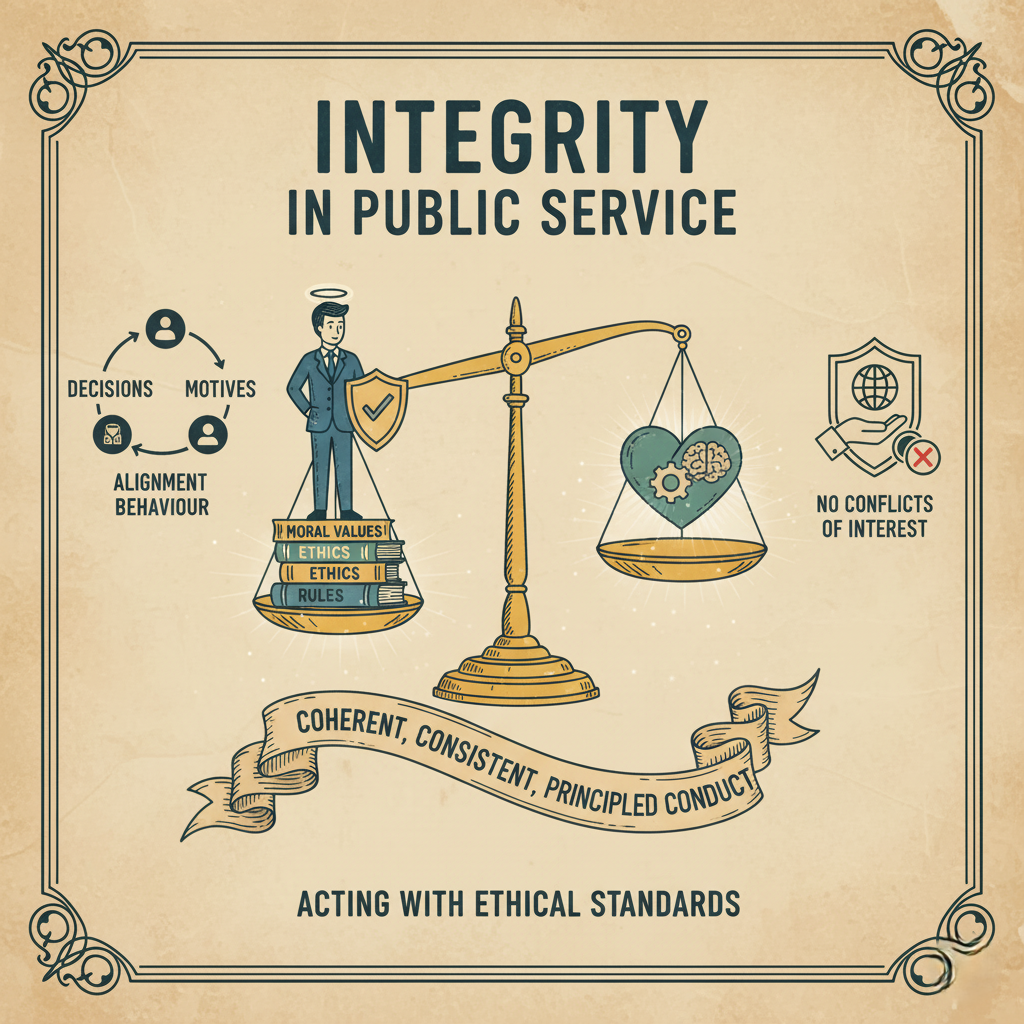

Integrity (broad): acting in accordance with a set of moral values, norms and rules in a coherent, consistent and principled way — not merely avoiding lies but aligning one’s whole conduct (decisions, motives, commitments and behaviour) with ethical standards. In public administration the idea also includes the avoidance of conflicts of interest and the protection of public interest.

Honesty (narrower): being truthful — not lying, not deceiving, and communicating facts accurately. Honesty is primarily about veracity and transparency in speech and records. The Nolan principles (widely accepted standards for public life) list honesty and integrity as distinct but related principles.

2. Conceptual contrast: integrity vs honesty — a structured comparison

- Scope

- Honesty is primarily cognitive/communicative: it concerns truthfulness in statements, records and representations.

- Integrity is systemic and dispositional: it concerns the alignment between values, motives, policies, and actions over time. Integrity includes honesty but goes beyond it.

- Direction of moral demand

- Honesty asks: “Are you telling the truth now?”

- Integrity asks: “Do your actions, choices and priorities cohere with ethical principles consistently — even when inconvenient?”

- Visibility

- Honesty is often visible in a discrete act (a truthful report, correct figures).

- Integrity is visible as pattern and character (consistently refusing undue advantage; institutional practices that prevent conflicts of interest).

- Institutional vs personal

- Organisations can embody integrity (codes, systems, culture) while individuals can exhibit honesty episodically. Institutional integrity requires structures, incentives and enforcement (e.g., an independent anti-corruption body). CVC

- Moral worth

- A person may be honest yet lack integrity (truthful about a small matter while tolerating systematic wrongdoing). Conversely, someone may show integrity by upholding public interest even when rare truthful slips occur — integrity is judged by pattern and principle.

3. Dimensions of integrity (useful for answers)

- Moral consistency: internal coherence between beliefs and actions.

- Independence from improper influence: resisting bribes, nepotism or sectional pressures.

- Transparency and accountability: openness about decisions and readiness to be scrutinised.

- Rule-respecting and rights-sensitive action: following laws and protecting legitimate entitlements.

- Courage of conviction: willingness to act ethically under adverse personal consequences.

4. Real-life illustrations

Illustration A — Honesty without full integrity

A local health department official files monthly expenditure reports that are factually correct (honest). But the official routinely assigns contracts to a friend’s firm without tendering and manipulates standards so that the friend’s low-quality work passes inspection. The official speaks truthfully on paper but suborns processes to favour a private interest.

Diagnosis: honesty (truthful reporting) but absence of integrity (failure of impartiality, conflict of interest and public-interest orientation).

Illustration B — Integrity that subsumes honesty

A district collector discovers that a politically influential contractor supplied substandard materials to a public housing project. The collector orders an independent quality audit, initiates disciplinary action, and declares the contractor’s links publicly despite political pressure and threat of transfer. The collector’s records, orders and public statements are truthful (honest) but more importantly her actions are consistent with duty, public interest and institutional rules.

Diagnosis: integrity in action; honesty is a component but the defining feature is principled, consistent behaviour.

Illustration C — Institutional integrity vs institutional dishonesty (case example)

Recent inquiries into the UK Post Office Horizon scandal showed systemic failures: sub-postmasters were prosecuted on the basis of faulty IT records; the institution repeatedly defended its position rather than transparently investigating the IT system’s faults. That episode is often analysed as a failure of institutional integrity (defensive posture, lack of accountability and opacity), not merely isolated lies.

Illustration D — Role of integrity institutions

An independent integrity institution (for example the Central Vigilance Commission in India) exists to preserve administrative probity by investigating corruption, issuing guidelines to avoid conflicts of interest and promoting ethical standards. Strong institutional architecture helps convert individual honesty into collective integrity.

5. Why the distinction matters for public servants (practical implications)

- Policy design: rules must aim not just to detect untruths but to remove perverse incentives that corrupt judgement (e.g., transparent procurement, asset declarations).

- Performance appraisal: assess patterns and decisions (integrity) rather than isolated truthful acts.

- Prevention over detection: Institutional integrity emphasises system design (checks, audits, rotation, declaration regimes) rather than only punishing dishonest remarks.

- Ethical leadership: leaders who demonstrate integrity (not only honesty) cultivate an ethical culture; this is a central Nolan principle.